Water Security in a Southern African Context: An Overview

Southern Africa has a total population of 68 million people, which will increase to 76 million over the next decade. Predominantly an arid region, two out of the five Southern African nations are classified as high water stress countries.

UN-Water defines water security as “The capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socioeconomic development, for ensuring protection against water-borne pollution and water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability.” Globally, 844 million people lack access to safe and affordable drinking water (UNDP), and around 90 per cent of them live in sub-Saharan Africa (UN data).

1. The particular case of Southern Africa

Water Security is a significant socioeconomic risk in Southern Africa. All countries (i.e., South Africa, Lesotho, Eswatini, Namibia, and Botswana – see UN scheme of geographical regions) are water-scarce or water-stressed or both (Chemonics). Botswana was classified as an extremely high water stress country in 2019 by the World Resources Institute (WRI). Namibia, one of the dryest country’s in the world, was classified as a high water stress country within the same ranking. At the same time, South Africa and Lesotho were both ranked within the medium to high range. For South Africa, one province, namely the Western Cape, is experiencing extremely high water stress levels. Lastly, Eswatini is ranked within the low-to-medium water stress level.

2. Main contributing factors to water insecurity

As suggested above, factors that are contributing to water stress and scarcity include climate change. In addition, a growing population, urbanisation, and socioeconomic development are also associated with the rise in the demand for water in these countries (ESI-Africa, WRI). For example, water demand from agriculture is on the rise in Southern Africa due to increasing food demand, and the latter is associated with a growing population (Greenwell Matchaya et al.).

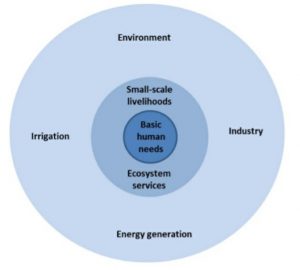

Figure: Important socioeconomic water uses requiring water security.

Source: National Water Security Framework for South Africa: 1st Edition, July 2020 (Page 4)

Indeed, these countries have two common challenges with regards to water security. The first one is to ensure access to water and sanitation for all by 2030, mainly in the rural areas (see SDG #6). The second one already suggested above is to strengthen resilience to climate changes, particularly drought and, to some extend, floods (see SDG #13, target 1) (Mike Muller).

3. Barriers to water security

However, during a 2016 interview of a selected group of water professionals in South Africa, identified four barriers to water security:

- Lack of adequate skills and

- Political will in government,

- A failure to use better quality water treatment technology, and

- Mistrust between communities and government when it comes to water service delivery (Sershen et al.).

Not surprisingly, a 2018 study by Mike Muller and a relatively recent UN-Water report suggests that the main barriers to water security in southern Africa are, in fact, the economic status and the institutional capacity. Because there is evidence that the challenges mentioned above discussed in point 2 of this article have been solved where there are quality institutions, effective cross-border cooperation, and access to sufficient financial resources for adequate investment in water infrastructure and human capital (Mike Muller, Jeremiah Mutamba). Indeed, greater cross-border harmonisation of national resources management policies in Southern Africa should be encouraged (Chemonics). For example, the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) provides water to South Africa’s Gauteng region and generate hydro-power for Lesotho (LHDA).

4. Other relevant policy prescriptions gleaned from the literature

a) Improve the efficiency of treatment of collected wastewater in Namibia (WRI) and invest in developing better and affordable water treatment technology via, for example, a significant increase of funding into water research scholarships.

b) Promote the use of low-flush toilets in new and old buildings to reduce wastage (James Cullis/ESI-Africa).

c) Promote seawater desalination in Cape town throughout the year (Jeremiah Mutamba).

d) Improve the human capital of water professionals via capacity building and training programmes to address the skills gap (Sershen et al.).

This article was written and published with permission by Hugue Nkoutchou, PhD (Bath)

For more information on Southern African markets or water projects in the region, please contact us here.